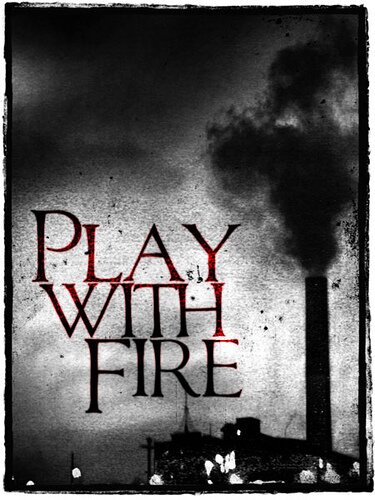

One of the cool things about being a movie blogger is getting approached by independent filmmakers who are looking for some help spreading the word about their projects. It’s a great way to get outside the Hollywood bubble and it’s refreshing to rub elbows with our fellow aspiring professionals and revisit the pure joy of film. The latest film to cross my path is a small town crime drama directed by Soren Johnstone called Play With Fire. It’s about a small time meth dealer living in a British Columbia mill town coping with pressures from within and without to make a change in his life. It’s a story about love, guilt and murder – but ultimately about despair, the despair of the cycle of crime and violence facing small towns across the country.

One of the cool things about being a movie blogger is getting approached by independent filmmakers who are looking for some help spreading the word about their projects. It’s a great way to get outside the Hollywood bubble and it’s refreshing to rub elbows with our fellow aspiring professionals and revisit the pure joy of film. The latest film to cross my path is a small town crime drama directed by Soren Johnstone called Play With Fire. It’s about a small time meth dealer living in a British Columbia mill town coping with pressures from within and without to make a change in his life. It’s a story about love, guilt and murder – but ultimately about despair, the despair of the cycle of crime and violence facing small towns across the country.

…the mill, dominating the town’s meagre skyline and set against such a rugged natural setting evoked images of The Deer Hunter…

Johnstone set himself the ambitious challenge of shooting the film entirely in natural light, and manages to capture Trail, BC’s beauty and misery at its most raw. From a noose dangling from a bridge in the noonday sun, to the monolithic mill looming over town, he establishes a post-industrial dystopia in the heart of the most beautiful place on Earth (that’s BC to the uninitiated). What stunned me was that the mill, dominating the town’s meagre skyline and set against such a rugged natural setting evoked images of The Deer Hunter, wherein we had the Vietnam war to bring the lives of its characters into focus. In Play With Fire there is no seminal event to help Christian sort out his problems, only the bleak prospect of either one day working in the mill or taking matters into his own hands by dealing meth to his similarly disaffected neighbours. The result is a community living in the shadow of the mill, wasting away on drugs, trying to stay away from it, but never being able to escape it.

Soren Johnstone’s naturalistic style should serve as an example to aspiring filmmakers that budgetary concerns don’t have to stand in the way of beautiful cinematography. The story is gritty, universal, and perhaps even a little too familiar, with surprisingly rich performances from an entire cast of non-professionals. It’s a testament to movie making in its most stripped down form and a must see for would be a valuable secret weapon in any young filmmakers arsenal. Keep an eye out for Johnstone’s name in the coming years, his talent is bound to land him higher profile gigs as word of his work spreads.